Murder, charm, pod, stand…

|

| From Pexabay.com (free images!) |

… they’re all supposed to be names for groups of animals. But are they, really? Or are they simply made up by someone as a kind of joke?

Such questions the enquiring mind wants to know! So, today, a fairly straightforward couple of questions that will open your mind to running down the true origins of words.

1. What are these kinds of terms called? (That is, what do you call words that denote a specific name for a group of a particular kind of animal, such as as “pack” of wolves.) What’s THAT called? (Once you know this term, perhaps it will be simpler to figure this out…

In this case I happen to know the term for a collection of somethings. If you’ve got a collection of things that are not meaningfully divisible, such as luggage or happiness, then that’s a mass noun. (Which, btw, is never used with the indefinite article! You wouldn’t say “a luggage” or “a happiness.”)

By contrast, the term for a collection of arbitrary things is a collective noun, words like crew, team, committee, or pack. This also includes collective nouns for animals: pod, swarm, flock, etc.

But for this Challenge, what’s the specific term for the collective noun of particular kinds of animals?

[ collective noun animals ]

leads to a bunch of great resources, including the inevitable Wikipedia page, List of Animal Names.

But if you look at the Wikipedia page for Collective Nouns, you’ll learn that

“…Some collective nouns are specific to one kind of thing, especially terms of venery, which identify groups of specific animals. For example, “pride” as a term of venery always refers to lions, never to dogs or cows. Other examples come from popular culture such as a group of owls, which is called a “parliament.”

I’d heard that term before, but couldn’t recall it without looking at that page. But let’s drill down a bit on that term (“venery”). Continuing farther down the page of Collective Nouns, we read:

“The tradition of using “terms of venery” or “nouns of assembly,” collective nouns that are specific to certain kinds of animals, stems from an English hunting tradition of the Late Middle Ages. The fashion of a consciously developed hunting language came to England from France. It was marked by an extensive proliferation of specialist vocabulary, applying different names to the same feature in different animals. The elements can be shown to have already been part of French and English hunting terminology by the beginning of the 14th century. In the course of the 14th century, it became a courtly fashion to extend the vocabulary, and by the 15th century, the tendency had reached exaggerated and even satirical proportions.”

There’s even a reference to several books, most notably the Book of Saint Albans (1486) which lists 164 terms of venery, many of which are clearly humorous, such as “a Doctryne of doctoris,” “a Sentence of Juges,” “a Fightyng of beggers,” “a Melody of harpers,” “a Disworship of Scottis,” and so forth.

Apparently, the Book of Saint Albans became very popular during the 16th century and had the effect of perpetuating many of these terms as part of the Standard English lexicon even if they were originally meant to be humorous and have long ceased to have any practical application. The popularity of the terms in the modern period has resulted in the addition of numerous lighthearted, humorous or facetious collective nouns. As has been noted, “Terms of venery were the linguistic equivalent of silly hats: colorful, affected, fashionable, and very popular. And like most jargon, they were ripe for parody.”

|

| Sample page from the Book of St. Albans (1486) |

But few of these terms were in common use after the 16th century. So why are they so well-known today?

Several of these sources point to the book, An Exaltation of Larks, by James Lipton (1968) as causing the revival of many of these terms of venery. In this book, Lipton goes back to fifteenth century manuscripts (such as St. Albans) and dug up terms for collections of birds and beasts and types of men that he wants to restore into English usage. That is, it was a very conscious attempt to return terms like “murder of crows” to common usage and make English more colorful. In this he seems to have succeeded.

Interestingly, the original subtitle of Lipton’s book was An Exaltation of Larks or, The Venereal Game. You now know that “venereal” is the adjectival form of “venery,” and not a reference to an STD, but you can also see why the publishers might want to change the title in subsequent editions. (Also, it is not to be confused with An Exaltation of Larks, #1 in the Venery Series, by Suanne Laqueur, a novel of family, terrorism, and romance.)

You should also know that Lipton clearly is inventing language just for the fun of it. His coinages include “a Kerouac of deadbeats” and a “chatter of finks.” Those probably aren’t in any original 16th century texts.

2. Where did the term “murder” as a term for a group of crows begin? (Mind you, just linking to a random website isn’t going to cut it in SRS-land. You need to have a highly credible source, which means you need to think about what counts as “credible” for etymological sources. It’s an interesting question.. what does count?)

As we just learned, many of these venery terms originated in the 16th century, but then seem to have fallen out of common use not long afterwards. Then, with the publication of Lipton’s book in 1968, they’ve become popular again, primarily as humorous, lighthearted, fun collective nouns.

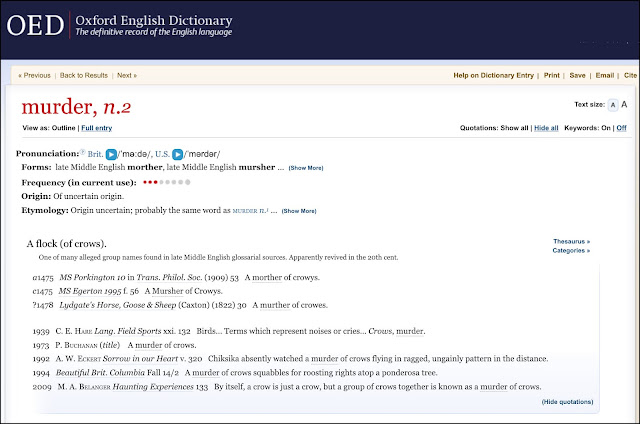

In the particular case, of “murder” for crows, probably the most authoritative source for the origin of English words is the Oxford English Dictionary, aka the OED.

The OED is the standard reference text for word origins (their etymology). If you’ve ever wandered in a library, it’s usually the largest book (or collection of volumes) in common use.

Luckily, there’s an online version of the OED.

Unluckily, it costs $100/year to access it.

Luckily, many libraries offer online OED access as a public service.

Unluckily, my local public library does not have this.

Luckily, I have a university connection that gives me online access.

So… I login to my university, connect to the library’s OED service and search for the word “murder.” And find the second definition:

|

| “murder, n.2”. OED Online. December 2021. Oxford University Press. https://www-oed-com.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu/view/Entry/244990?rskey=k58qLi&result=2 (accessed December 01, 2021). |

As you can see, the OED dates the use of “murder of crows” as a collective noun to 1475 in the Porkington manuscript (reported on in the Transactions of the Philological Society in 1909) where it appears as “a morther of crowys.”

The Porkington text:

“Written on paper and parchment, it contains a remarkable variety of texts, mainly in Middle English though a few are in Latin. These cover subjects from political prophecy to instructions for computing the position of the moon, from weather lore to medicine, from an Arthurian poem relating the adventures of Sir Gawain to saints’ lives, and from love poetry and drinking songs to carols. One text defines the qualities of a good horse, another gives lists of terms relating to hunting game – and to carving the game when it reaches the table...”

So, “murder” as a collective noun has a long history, dating at least back to 1475, but its rate of use is a relatively recent phenomenon:

|

| Google NGrams comparing “flock of crows” with “murder of crows.” |

3. What about a “Charm” of hummingbirds?

If we do the same OED search for “charm,” we have a different kind of result.

Checking the OED, we find no mentions of hummingbirds, but we DO see a reference to a “charme of birdes” and of angels (1548)! Elsewhere in the OED you can find a “charme of finches” as well.

Interestingly, other dictionaries (e.g., Merriam-Webster) have no mention of “charm” as a collective noun. And checking NGRAM again:

|

| Looks suspiciously like “charm of hummingbirds” started appearing after 1970 |

Surprisingly, Lipton’s book doesn’t mention a “charm of hummingbirds,” but instead refers to that group as a “shimmer of hummingbirds” (p. 274) He does mention a “charm of finches,” but that’s not quite the same thing.

The first use of this collective term in Google Books can be found in Tom Stoppard’s play, “Enter a Free Man” (1978).

If you check archival newspapers (e.g., Newspapers.com), you’ll find that the term starts appearing in the early 1980s, usually pointing back to Lipton’s book as the source, which is odd, because “charm” is used for finches, not hummingbirds. My bet is that someone took license with Lipton’s text and created the “charm of hummingbirds” (rather than of finches) somewhere around the mid-1970s. It’s such a perfect term that it started to be used more widely.

It’s beginning to a look a lot like Lipton’s goal of adding some fun and joy into our common language has succeeded. As he wrote: “What is more important is that a charm of poetry will have slipped quietly into our lives.”

4. And what about a “Mess” of iguanas? (Is that term for real? Or did someone just make it up for fun?)

NGRAMs tells us that “not enough data to plot.” And checking archival news gets us back only to 2012 (Austin American Statesman, July 1, 2012). OED doesn’t mention mess as a collective term except for people eating together (“the mess of soldiers”) and as a general term for collections (“a mess of eels” or a “mess of milk”–neither of which is specific to that kind of thing).

So I suspect that “mess of iguanas” is a general categorical term, much as you might describe that pit of snakes under your house as a “mess of snakes.” I don’t actually believe there is a single venery term for a collection of iguanas.

5. And lastly, what do you call a bunch of kangaroos? How old is THAT term?

Checking back on the Wikipedia page for animals, we find that a collection of kangaroos (dare I say “mess of kangaroos”?) is called either a court, a troop, a herd, or a mob.

NGRAMs, to compare the most common uses of the kangaroo venery terms:

|

| NGRAMs comparing “mob of kangaroos” with “troop of kangaroos.” “mob” leads, but there are a set of people who use “troop”! |

We need to bear in mind that the term “kangaroo” only entered into common English usage in 1773 (per OED: “1773 J. Hawkesworth Acct. Voy. Southern Hemisphere III. 578 [1st Voy. Cook] The next day our Kangaroo was dressed for dinner and proved most excellent meat.”)

The first archival newspaper mention of a mob comes from the North Wales Chronicle (Wales), July 8, 1845. In the story, Dan (not me!) is being carried away by a rogue kangaroo, and the author writes that not only would he not intervene, but “I wouldn’t have saved him from a mob of kangaroos…”

SearchResearch Lessons

Language is as language does–it’s fairly hopeless to be prescriptivist about these things. But it’s pretty clear that some terms of venery really are ancient, but then fell into disuse, and were then revived in our lifetimes. The fact that we can figure out such things is a testament to the coverage of online content.

But let’s touch on a few lessons to close out today’s SRS.

1. Etymology is tricky–you need to use multiple sources to triangulate on a trustworthy story about the origins of a word or phrase. Here we used a combination of newspapers, books, and dictionaries (especially the OED) as reference sources. It’s tempting to do a quick Google search and find a story about word origins, but be sure to get a few confirmations (and NOT just duplications) of the story. If you can find the word in actual use in an actual original source, so much the better.

2. The OED is a great resource. It really is a masterwork. (See: The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary: Simon Winchester, 2016, for the whole amazing backstory of how the OED came to be. In the tale you’ll learn why it’s such a remarkable and trustworthy source.) More to the point, it is the master reference on matters etymological in English, especially for older terms. (Since it’s updated infrequently, it’s not so great to the origins of recent terms such as “deplatform” or “cubesat.”)

3. NGRAMs can be used to compare phrases and their occurence (in books) over time. I’ll write more about NGRAMs in a future post, but note that you can now compare different corpora (e.g. British English vs. American English)

Search on!