… if you can find them… AND if you can understand them.

I have to admit that I spent a LOT of time on this Challenge. It was just a fascinating bit of research. The more I dug, the more I found. At this point, I could write a book! But that’s not on the agenda. Instead, this post is really focused on what I did to find the information, how I did it (and then a little bit about what I found).

Reading through old news is incredibly illuminating, especially when you’re reading about past pandemics–it doesn’t get any more fascinating than this.

1. Can you find articles from the news archives of 1918 and 1919 that will show us what happened back then, and MORE IMPORTANTLY, give us a clue about what might happen in the months and years ahead?

Searching in older content requires a bit of thought. The farther back you go, the more you notice that the way people spoke and wrote in the past is a bit different than the way we do now.

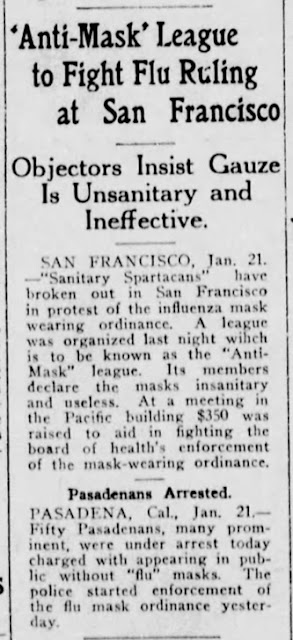

Here’s an article from the LA Herald (Jan 21, 1919) about the “Sanitary Spartacans” and the “Anti-Mask League” meeting to raise money to fight the mask-wearing ordinance. I just found this while searching through a news archive, searching for “San Francisco” and “Spanish flu.”

|

| LA Herald (Jan 21, 1919) |

Orienting with a timeline:

To begin, I noticed that NPR commentator Tim Mak wrote a truly remarkable (and lengthy) blog post about the parallels between the COVID-19 pandemic and the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. This is a great source of ideas, but more importantly–it points out that a timeline and current historical documents are an incredibly useful thing to have as a way to structure our search into the archives. Let’s look for some other timelines:

[ timeline Spanish flu ]

Yields a lot of timelines. A really interesting timeline came from the American College of Emergency Physicians, which contains this bit about the end of the pandemic:

Nov. 21, 1918. Sirens sound in San Francisco announcing that it is safe for everyone to remove their face masks.

Dec. 1918. 5,000 new cases of influenza are reported in San Francisco.

Jan. 1919. Schools reopen in Seattle.

March 1919. This is the first month that no influenza deaths are reported in Seattle.

Obviously, San Francisco made a huge mistake in declaring the Spanish Flu to be over.

In looking at the CDC’s timeline, we learn that:

March 1918. First wave of Spanish flu in the US

Sept-Nov 1918. Second wave of flu (somewhat more lethal)

January, 1919. A third wave of influenza, subsiding by summer, primarily in Europe

January, 1919. San Francisco: 1,800 flu cases and 101 deaths are reported in first five days. Many San Antonio citizens complain that new flu cases aren’t being reported.

It’s easy to search for current historic documents with a search like:

[ history of 1918 flu ]

A search like this gives lots of articles. (Example: Washington Post, “To save lives, social distancing must continue longer than we expect: The lessons of the 1918 flu pandemic” which points out that cities such as Denver had a second wave of flu illnesses in December, 1918, rolling into January and winding down by late spring.

More to the point, for our purposes, these kinds of timelines and retrospective articles give us some dates, language, and ideas to search for in our archival newspaper search.

Finding Newspaper Archives:

Obviously, you’ll need to first figure out how to access and search through news archives. (See my earlier SRS post about this: Online News Archives and another one for some tips about how to do this.) The simplest way is to search for:

[ list of newspaper archives ]

which will quickly take you to the great Wikipedia list of digitized newspapers that covers the US and many other countries.

From that list I mostly chose to use the Library of Congress Chronicling America site, and the California Digital Newspaper Collection. Both have extensive collections and cover the years 1918/1919. (For backup, of course I’d check the Google News Archive. That archive has a very different set of sources that either Chronicling America or the CDL.)

In addition, I know about and use the commercial site Newspapers.com, which has a really marvelous search interface (and their display interface is, without question, the best in the business). It costs real money, but some public libraries offer access (through their web portal), and many (nearly all?) university libraries have access to them as well. This is yet-another reason to hang onto your university/college library account for as long as they’ll let you!

In all cases, you probably will want to use the the advanced search interfaces. They give you a LOT more control over what you’re searching for. Here’s the LOC’s advanced search interface.

Note that you can select the newspapers, or all papers in a state, give a date range, and specify your search with ANY (that is, OR), with ALL of the terms, or with a phrase (that is, like a double-quoted Google search).

Finding great search terms:

As noted, the language of 1918-1919 is a little different than what we use today. The trick here will be to find the right search terms that will let you discover the major events of the pandemic, and what we should look forward to. Off the top of my head, I wasn’t sure what to search for to get into this topic. It’s useful just to start reading some articles and begin taking notes about terms you find.

I’m a real advocate for notetaking as you do your research, and in this case, I just created a Google doc and poured lots of thoughts, links, and ideas into it. That becomes my “notes bucket.” In particular, I’m taking notes on the terms and language used at the time. (Here’s my example of a notes bucket about Spanish Flu.)

This means that you’ll be able to focus your research questions as you read along. Some special terms from that time are: “Anti-Mask League” “sanitarian” “Public Health Board” and so on. (See the notes for more.)

Let’s look at some of the questions that I asked:

a. How did your nation recover from the economic downturn caused by the Spanish Flu? What articles can you find that tell us what to look for?

This turned out to be a rather difficult question to answer! World War 1 had been raging since 1914 and ended on November 11, 1918… which tangles up economic recovery from the war with economic recovery from all of the Spanish flu misery. (I tried various queries, but it’s a real confusion of results. This is probably better answered by more recent economic analysis such as that of Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner (from the US Federal Reserve) who write that:

“While non-pharmaceutical interventions [e.g. social distancing, slowing contact rates, etc.] lower economic activity, they can solve coordination problems associated with fighting disease transmission and mitigate the pandemic-related economic disruption… ”

They go on to say that the increase in mortality from the 1918 pandemic (relative to 1917 mortality levels, which was 416 per 100,000) suggests a 23 percent fall in manufacturing employment, and a 1.5 percentage point reduction in manufacturing employment to population.

In other words, a big outbreak spelled economic disaster for affected cities. But they found that the introduction of social distancing policies is also associated with positive outcomes in terms of manufacturing employment and output. Cities with faster introductions of these social distancing and mask policies had 4 percent higher employment after the pandemic, while ones with longer durations had 6 percent higher employment after the disaster. That’s a huge surprise.

In other words, social distancing measures that save lives can also, in the end, soften the economic disruption of a pandemic.

The takeaway is clear: These policies not only led to better health outcomes, they in turn led to better economic outcomes. Pandemics are very bad for the economy, and stopping them is good for the economy.

But… I couldn’t find this easily in the archival news. It’s only with the distance of time that these results became evident. Sometimes, you just have to wait for history to catch up.

b. How well did the protests against mask measures work out? Were the protesters successful? What happened to the number of flu cases after people stopped wearing masks?

On the other hand, this was a straightforward Research Question to answer. We already found the “Anti-Mask League” which appears in multiple newspaper accounts in early 1919, as well as the proceedings of the Board of Supervisors for San Francisco, January 1919. Here, the Anti-Mask league petitions for relief from “the burdensome provisions of this measure.”

Note how similar the argument is between then and now. “.. it was not in keeping with the spirit of a truly democratic people to compel people to wear the mask that do not believe in its efficacy…”

Using a special term (like “Anti-Mask”) works well. But I also found good results by date-restricting my archives searches to 1918-1919 and doing searches like:

[ “Spanish influenza” mask protest ]

The bottom line here is that protests about wearing masks was fairly common. As we’re seeing today, people hated wearing masks. Police enforced mask-wearing (at least in San Francisco), but it was always a tense and difficult situation, even though then, as now, it’s clear that masks really do help suppress the spread of the infection.

|

| San Francisco Examiner, Jan 20, 1919 |

|

| San Francisco Chronicle, Nov 2, 1918 |

Interestingly, one of the things I picked up in this search is that not all of the news archives are equal in coverage or scope!

For this search, there were no hits in the California News repository, but over 100 in the Library of Congress collection, and over 30 in the Google News Archives. Moral here–for complete coverage, you have to check multiple sources with variations on your query to make sure you find what you seek.

c. Was the course of the Spanish Flu pretty simple, or was it (as some have predicted about COVID), fairly up-and-down for quite a while after the initial outbreak?

Searching for orders imposing masks or limiting movement wasn’t hard, but it was a bit tedious. With a search like:

[ “Spanish influenza” health board orders ]

it was easy to find when bans were imposed, but finding the removal of the orders was tricky. Often, a search like:

[ “Spanish infuenza” lifted OR removed

orders health board ]

would find the lifting of a ban that was issued by the local health board, but it was a little hit-or-miss. I could FIND them, but it was quite a bit of clicking and looking around to find a ban’s imposition and then removal… and then re-imposition, and re-removal…

Here’s one example:

In this case, the article tells us that it was imposed on Oct 7, and then lifted on December 18, 1918. (And yes, the mayor had to reimpose the ban in early 1919.)

d. Why did the Spanish Flu finally go away? (Or did it?) Did someone develop a vaccine for it, or why did it stop being a pandemic?

This was a hard one. It was like looking for a non-event. The best approach here was to search for articles that were retrospective articles. That is, there’s little point in looking for the end of something when you’re not sure if the end has happened yet!

Apparently, the Spanish flu just vanished. In the archival record there’s a diminishing of articles over time, but no clear “The End!” articles were written.

Wikipedia helpfully tells us that “…Another theory holds that the 1918 virus mutated extremely rapidly to a less lethal strain. This is a common occurrence with influenza viruses: there is a tendency for pathogenic viruses to become less lethal with time, as the hosts of more dangerous strains tend to die out.”

This is a lesson too… It’s hard to look for the absence of something, or the unclear and uncertain ending of an ongoing event… Like the end of the flu.

Search Lessons

There are many here:

1. Timelines are great to orient you and give you times / topics to search for. This is good advice anytime you start doing research on a particular topic. Get a headstart by looking for something that organizes the events and times you’re looking for… And mine it for key terms, names, and phrases.

2. You need to use multiple online archives. In this case I used 4 different archives (Library of Congress, California Digital News, Google News Archives, and Newspapers.com). A careful researcher will want to cross-check over multiple collections. No one resource has it all!

3. Different archives have very different search capabilities. Some don’t have a good advanced search function (the ability to filter metadata such as “state of publication”), although all offer date limits. Some handle double quotes correctly, others are a bit lax in their interpretation. It’s usually worth spending a little time figuring out how this particular archival search actually works.

4. Sometimes the original source material is too close to the events of the time for good archival search. Figuring out the economic effects of the pandemic isn’t something that’s written about a lot at the time, but can be figured out much later, when researchers can synthesize data from multiple sources over a longer period of time.

5. News archival search isn’t easy or fast. Settle in and enjoy the searching because it takes time to mine the past.

6. Learn the terms of the past. As you see in the above examples, you sometimes need to pick up specialized terms that you might not use in everyday life today. (I never use the term “Health Board,” although it’s a very useful term when searching for medical events in the early 20th century!)

I hope this was useful… Knowing these lessons will definitely be handy when you next do an archival news search!

Search on!