The basic question from last week’s Challenge was “What was the original or natural range of these three animals?” (Lion, Ground Sloth, Camel) It’s a natural enough question, but the answers can be surprising.

The Challenge was:

If there were, once upon a time, lions and camels and ground sloths (Oh my!) in North America, what was their historic region? During the past 100,000 years, where could you find camels, lions, and ground sloths?

Basically what we’re looking for is a map of the ranges of these animals. But… it’s tricky. The obvious queries like:

With questions like this, we need to be very clear about what our terms actually mean. It sounds obvious, but what, really, is a lion?

For instance, it’s easy to find this map from the above query on Wikipedia:

|

| “Historic lion range” per Wikipedia |

What do you mean by “lion” and what do you mean by “historic”?

Reading the Wikipedia article about lions we find: “In the Pleistocene, the lion ranged throughout Eurasia, Africa and North America from the Yukon to Peru..” Really? There were lions in North America?

We must go deeper.

And it doesn’t take us long to learn that there are extinct subspecies of lions, and that today the American lion that lived during the Pleistocene is usually treated as a sub species of the African lion (Panthera leo), which is why it is more commonly listed as Panthera leo atrox. However there are a number of researchers who consider the American lion to be different enough from the African lion to give it its own distinct species of Panthera atrox.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg when dealing with the classification of the American lion and it’s easy to become lost in all of the multitude of theories and arguments about its true position in the Panthera clan.

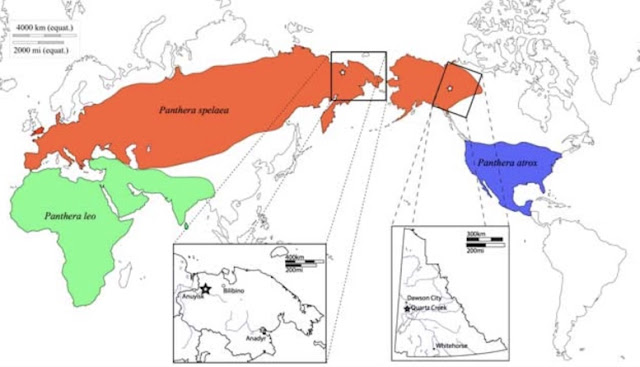

Of course, there’s another lion that’s known from its bones, the Eurasian cave lion (Panthera leo spelaea), which is itself another kind of closely related lion that went extinct about 13,000 years ago. This similarity has been confirmed by mitochondrial DNA analysis which shows that the American lion and Eurasian cave lion were almost identical, although the American does seem to have grown slightly larger. (See the Wikipedia article about leo spelaea.)

So if we look for range maps for each of these subspecies of lion (notice how I’m looking for this particular species name, not just for lion):

[ map range Panthera leo spelaea ]

we’ll see a number of maps, such as this one:

|

| Historic range (13,000 years ago) of Panthera leo spelaea (From a paper on its genetics) |

Although even this map seems a little incomplete–as we see in the Encyclopedia of Life entry about the American Lion, its range went down into northwestern South America. (Another article about lions in South America.) It never lived in Australia or Antartica, but something very much like a lion seems to have lived just about everywhere else.

So… what’s its original range? Well, there were lions just about everywhere–in North and South America, as well as all of Africa, most of Europe, and vast swaths of Asia.

What about the ground sloth? We don’t see them roaming around anywhere these days. So what was their original range?

Let’s go back to our previous question: What do you mean by ground sloth?

The Wikipedia article on ground sloths seems fairly complete. It tells us that (summarizing here):

Ground sloths are a diverse group of extinct sloths in the mammalian superorder Xenarthra…. a term used as a reference for all extinct sloths because of the large size of the earliest forms discovered, as opposed to existing tree sloths…

Much ground sloth evolution took place during the late Paleogene and Neogene of South America while the continent was isolated. At their earliest appearance in the fossil record, the ground sloths were already distinct at the family level. The presence of intervening islands between the American continents in the Miocene allowed a dispersal of forms into North America. A number of mid- to small-sized forms are believed to have previously dispersed to the Antilles. They were hardy as evidenced by their diverse numbers and dispersals into remote areas given the finding of their remains in Patagonia (Cueva del Milodón) and parts of Alaska.

Sloths, and xenarthrans as a whole, represent one of the more successful South American groups during the Great American Interchange. During the interchange, many more taxa moved from North America into South America than in the other direction. At least five genera of ground sloths have been identified in North American fossils; these are examples of successful immigration to the north.

(And, yes, I checked other resources about camels, e.g., books about camel evolution. This story checks out.)

Reading through this, we see that ground sloths (the Xenarthrans) inhabited at least North and South America, from Patagonia to Alaska… AND much of the Caribbean! That’s a huge range. Some varieties were just gigantic–five tons in weight, 6 meters (18 feet) in length, and able to reach as high as 17 feet (5.2 m). These were significant megafauna of the American landscape.

One particular kind of ground sloth has a special place in American history (which we’re celebrating today, July 4th). The megaloynx ground sloth was first identified by Thomas Jefferson in a paper that he presented before the American Philosophical Society on March 10, 1797: “A Memoir on the Discovery of Certain Bones of a Quadruped of the Clawed Kind in the Western Parts of Virginia.”

This paper is widely seen as establishing the science of vertebrate paleontology in the US. Interestingly, Jefferson identified the Megalonyx as a giant lion, and asked Lewis & Clark to be on the lookout for any Megalonyx as they explored the American west in their expedition of 1804 – 1806. Jefferson, along with many other scientists of the time, had no idea that animals could go extinct, and so he naturally saw these bones in terms of existing animal forms. Alas, he missed the last Megalonyx by a few million years.

But their range was clear: It varied by species, but collectively, the ground sloths were found in the Americas.

Finally, what about camels?

Again I have to ask: What do you mean by camels?

If we check the Wikipedia page on camels, we learn that dromedaries live in the Middle East and the Horn of Africa, while Bactrian camels are native to Central Asia, but live throughout remote areas of northwest China and Mongolia. (Historically, the area known as Bactria is the flat region straddling modern-day Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. More generally, Bactria was the area north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Tian Shan with the Amu Darya flowing west through the center.)

But we also learn that an extinct species of camel in the separate genus Camelops, known as C. hesternus, lived in western North America before humans entered the continent at the end of the Pleistocene.

This takes us, once again, into a definitional moment.

Looking up the evolution of camels, we learn that the earliest known camel, called Protylopus, lived in North America 40 to 50 million years ago. It was about the size of a rabbit and lived in the open woodlands of what is now South Dakota. 35 million years later, the Poebrotherium was the size of a goat and had many more traits similar to camels and llamas.

But the direct ancestor of all modern camels, Procamelus, lived in North America around 3–5 million years ago. This proto-camel species, Camelidae, spread to South America as part of the Great American Interchange, where they gave rise to guanacos and related animals. They also spread to Asia via the Bering land bridge, including Ellesmere Island (in modern Canada, well above the Arctic Circle, near Greenland).

|

| Procamelus from the mid-Miocene in Colorado, by Robert Horsfall. (p/c: Wikimedia, from the book A history of land mammals in the western hemisphere by William Berryman Scott) |

The Wikipedia article on camels tells us that the “last camel native to North America was Camelops hesternus, which vanished along with horses, short-faced bears, mammoths and mastodons, ground sloths, sabertooth cats, and many other megafauna, coinciding with the migration of humans from Asia.”

Well, that’s interesting: the American Lion, ground sloths, and camels all went extinct around the time humans appeared in the Americas.

So if we consider as camels only “large animals with humps” (and not the smaller camelids like llamas and guanacos), their range was historically North America, then spreading into central Asia and the Middle East.

If you search for other possibilities (e.g., [ Europe camel] or [Africa camel]) all you’ll find are references to the (relatively recent) introduction of camels into those places.

Likewise, camels seem to have spread a bit more recently into places you might not have expected.

Around 700,000 dromedary camels are now feral in Australia, descended from those introduced as a method of transport in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This population is growing about 8% per year, even becoming a problem as they consume resources in a limited landscape.

In North America, after being away for a 15,000 years, a small population of introduced camels were imported in the 19th century as part of the U.S. Camel Corps experiment. Never a full part of the Army, it was a short-lived experiment to use camels in arid climes instead of horses. When the project ended a few years later, they were sold to be used as draft animals in mines, some escaped, or were released in to the desert. Twenty-five U.S. camels were bought and imported to Canada during the Cariboo Gold Rush. (NYTimes article about the Camel Corps.)

|

| Upon finding water during a surveying trip, horses would drink immediately, while the accompanying camels would show little interest (see the camels in the upper right background). The Army’s camels proved they could withstand the oppressive climate of the American Southwest and other hardships that could send horses and mules into a panic. (Horses Quenching Their Thirst, Camels Disdaining, by Ernest Etienne de Franchville Narjot, courtesy of The Stephen Decatur House Museum) |

Search Lessons

There are two big lessons here (and one little one).

1. Be clear about what you’re searching for! In the case of the lion, do you mean to include American Lions? Or only the African variety? In our case, we chose to go with clearly related (albeit extinct) lions (e.g., the Cave lion and the American lion). This changes your search strategy to include very specific terms, like Panthera leo spelaea, or Pathera atrox. Likewise, we had to make a cutoff for camels since the evolutionary slope is a bit slippery. We didn’t want to include camelids like llamas, so we went with “big cloven footed animalas with humps” which evolved at a particular time. (Note: camels and llamas can interbreed, although like mules, the offspring is sterile… so we chose a morphological cut-point, rather than a clear species boundary.)

2. Checking Images is sometimes helpful for finding maps that give extents. As a general strategy, I often check Google images for information that’s presented graphically, using the same queries as I use when searching the web. About half the time, I end up learning something that I hadn’t anticipated learning. Serendipity is your friend, and Image search lets serendipity happen!

3. (A small point) I found the image of the Procamelus not by doing “regular” web search, but by searching on Wikimedia. Normally, I think of Wikimedia as being the repository for all of the images on Wikipedia, but sometimes you can find images that appear only in the Wikimedia collection that don’t seem to appear anywhere else in Wikipedia. This is incredibly handy for teachers (and blog post writers) because they come with the copyright information and are often uncommon images. It’s easy to search this space, just use a site: query like this: [ site:wikimedia.org procamelus ] You’ll find all of the images you might need, along with useful copyright information.

Ending note:

This week’s post took longer than normal for a couple of reasons–the book needed attention, I had a few things to do at work, and there was a bug in Blogger than I needed to run down. (One of the downsides of working at Google is that I feel obligated to help find bugs in our products. C’est la vie.)

As I was feeling bad about being slow to stick to the publication cycle, I realized that the rest of the summer is going to be busy as well. I’m teaching a few search classes in Europe, and taking a bit of vacation in places that won’t have Wifi, nor will I have my computer. These places should be fun, and should lead to even more interesting SearchResearch Challenges.

I’ll keep writing, and will write something every week (unless I know I’m going to be off the grid, but I’ll give a heads-up when I know…).

Until then, Search on!