Trying to find answers is easy…

… sometimes. This week’s Challenge is a great mix of straightforward and complex. Let’s dive right in.

The Challenges were:

1. “Slagbaai” is the name of a large park on Bonaire. What does the name Slagbaai” mean?

As most everyone figured out,

[ Slagbaai ]

gives a pretty good answer. In particular, the second result, stinapabonaire.org/washington-slagbaai/ is the “official” national park web page. You can read the page to learn that “STINAPA N.A.” is a Dutch acronym, Stichting Nationale Parken Nederlandse Antillen, which is the national park system of the country. Check out the lovely overview video (with killer drone shots) on that page (at the very top).

On that page, you’ll get a short history of Slagbaai, but not a definition of what the word means. You have to click around a bit (or search for [what does Slagbaai mean ] and click on the STINAPA page that answers the question. To quote from their page:

The name ‘Slagbaai’ is often said to derive from the Dutch word ‘Slachtbaai’, meaning slaughter bay. Historians, however, say the name more likely originates from salt harvesting activities since the times of the original Indian population. In the past the bay was called ‘Sla baai’. ‘Sla’ comes from the Papiamentu word ‘salu’, meaning salt.

I’m going to accept their story (stories!) as the best authority for this Challenge. They’re locals. They also know the local language, Papiamentu. And it could well be that both stories are correct. Etymology is complicated, especially in places where creolization happens.

2. Bonaire is now a desert island, but it used to be covered in a forest that was dominated by a particular kind of tree. What kind of tree was so dominant? Why was it heavily logged?

I searched for:

[ history of trees on Bonaire ]

This finds a variety of sources. A good one is the Blue Oceans page. Here we find that there are 5 major kinds of trees on Bonaire.

Tabebuia Billbergi (Kibrahacha tree): blooms rarely; very hard wood; grows everywhere.

Bourreria succulenta (Watakeli) grows to about 7-8 meters;

Caesalpinia coriaria (Divi-divi tree) grows pods which contain large amounts of tannin, useful for tanning hides–and an export product for a short time.

Guaiacum officinale (roughbark lignum-vitae, guaiacwood or gaïacwood) is a species of tree in the caltrop family, Zygophyllaceae, native to the Caribbean and the northern coast of South America. Used primarily for medicinal purposes and incredibly tough wood (which would be used for ship pulley-blocks).

Haematoxylon brasiletto (Brazil tree, aka Palu di brasil, Brazil, Brazia, Stokvishout, Dyewood, Verfhout, dyewood). The dyewood has a distinctive, twisted shape and a deeply grooved trunk. The oldest known map of the Caribbean (from 1513) labels the island as “Ysla do Brasil” (“Island of the Brazil tree”). The Dutch seized Bonaire from the Spanish in 1636 in part to gain access to this commercially profitable product. In former centuries the wood was used to prepare a red dye. The wood was shipped to Holland where it was shredded in a “rasp house” to extract the dye which was then used to color cloth, hence the name Dyewood.

In the process of doing this research, I happened to run across this early map showing Bonaire:

|

| Excerpt of the 1513 map of the world, highlighting Bonaire (“Ysla de Brazill”). See arrow and filled-in island boundary. |

After getting this basic information, I then searched in Books and found several books that mention trees and forests on Bonaire, the most intriguing one is “A Short History of Bonaire, which includes a couple of intriguing comments. The Dye-wood tree was apparently all over the island AND all over Klein Bonaire (the circular, nearly perfectly flat island nestled in the bight of western Bonaire). “In 1623 a Dutch vessel cast anchor off Bonaire, and the sailors were at once struck by the fact that there was such an abundance of dye-wood standing about the island which, mor over, grew conveniently close to the shore.” (p. 15)

Later we find that “In the 17th century this little island was covered with it. Here too, ruthless cutting destroyed the trees.” (p 32)

Alas, we also read the “the guaiac or wayacá trees suffered the most destruction…. it was a great piece of good fortune for the island that, owing to a lack of shipping facilities, this unwise wasteful felling of trees was checked somewhat.”

So, both kinds of trees were heavily logged, but the Brazil tree / dyewood seems to have had the largest range, and therefore the most damage.

|

| Brazilwood tree (in Brazil) |

3. Can you find an early / historic period image of Bonaire? (The earliest image wins!)

This was a pretty ambiguous question on my part. Sorry about that. When I read Jon’s comment “.. just what DR means by historic period?” I realized that I’d left the question pretty open-ended.

This question COULD MEAN “an image of Bonaire made within the historic period” OR “an image on Bonaire that was made in prehistoric times.

In searching for the answer to the previous Challenge, I found that 1513 map. Finding that map was intriguing, so I kept looking for more early maps. I found that by searching for:

[ map Bonaire 16th century ]

I could find another map from 1522. (I kept looking but these were the earliest maps I could find.)

|

| Subsection of 1522 map of the coast of Venezuela (Getty Images). Here, north is to the bottom, and an inaccurately drawn Bonaire is on the far lower left of the map, with Curaçao and Aruba to the right. |

But I really was looking for earlier For the “within the historic period” version, I naturally looked at Bonairean history books–again looking on Google Books for

[ History of Bonaire ]

We know that in 1499, Alonso de Ojeda arrived in Curaçao and visited a neighboring island that was almost certainly Bonaire.

So, in a way, the earliest European image of Bonaire is that 1513 map from above.

BUT if you want something more like a “traditional” image, a quick scan through a few history books shows things like this:

|

| Photo of Fort Orange, Bonaire. 1896 |

|

| Krajlidihk, 1913. (From Wikimedia) |

In both cases, I found the images in history texts, and did Search by image to find other sources. I found a nice quality image in Wikimedia of the “Gezicht op Kralendijk.” For older images, you can almost always do this and work around copyright issues. (That is, find it in an open-source collection.)

To find prehistoric images on Bonaire, I did a search for:

[ prehistoric artwork on Bonaire ]

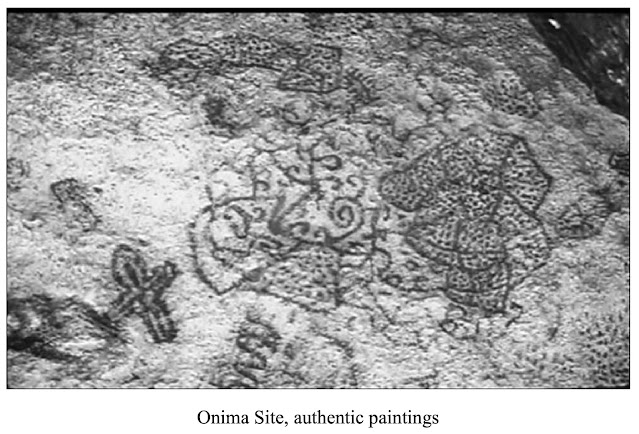

which took me to a bunch of resources, although perhaps the most interesting was a research paper “Distinguishing authentic prehistoric from historical replication rock painting features at prehistoric sites on Bonaire” published in the proceedings of the 21st International Association for Caribbean Archeology.

The paper is about the problem of accurately identifying prehistoric rock art from fake prehistoric paintings (and the modern “updates/improvements” to the underlying rock art).

In that paper, the following image is presented as original rock art from the Ceramic Period (450 – 1500 CE).

That’s a pretty broad range of time, but it’s definitely before any European maps were made, so I’d have to give this image at the Onima Site award as the “earliest image” of Bonaire.

4. I saw flamingos on Bonaire. Growing up, I saw lots of National Geographic specials on TV that told me they lived in Africa! Are flamingos native to the area, or were they imported? Have they always been on Bonaire?

|

| Flamingos on the solar salt ponds on the south part of the island. |

This wasn’t hard, but it was a surprise–my intuitions about flamingos being only in Africa was dead wrong.

“the family Phoenicopteridae, the only bird family in the order Phoenicopteriformes. Four flamingo species are distributed throughout the Americas, including the Caribbean, and two species are native to Africa, Asia, and Europe.”

Finding this was pretty straightforward, but the results are fascinating!

SearchResearch Lessons

1. Some research Challenges are complicated. Finding the original trees of Bonaire wasn’t hard, but finding which was the dominant tree, and why it was so aggressively removed, took a bit of reading.

2. You find things by reading widely. In our case here, as I was reading about the trees, I found an early map. That turned out to be handy when (later) I was searching for early images of/about/on Bonaire. The earliest maps are pretty interesting “images” of Bonaire, suggesting that it was a real place, even if the map outline wasn’t especially accurate.

3. Research questions need careful descriptions to know what you’re really searching for in your quest. SRS Regular Reader comments made me realize that my Challenge was “open-ended.” That’s what made me realize that a map would be an “early image of Bonaire” AND that prehistoric rock art would be an even EARLIER depiction of life on Bonaire. I wrote the Challenge without providing enough details to tell when you’d found an answer. (Teachers: Pay attention! Writing research questions is a tricky business. Be sure that you know what kinds of results would be good answers.)

Footnote: Sorry about this Answer being so late this week. It was a busy, busy, busy week. I’m glad I got this post done today! I’ll be back on Wednesday of next week to do the next one. It will be a bit more complex… so look for it then.

Search on!