One of the stranger things you’ve seen...

but perhaps hadn’t thought about… is the strange way in which older texts are capitalized. Noticing this led me to our most recent Search Challenge which asks why the capitals seem scattered almost at random:

|

| Printed copy of the Declaration by John Dunlap, 1776. Source: Library of Congress. |

1. What’s the story with the Capital letters in the 18th century? Were they just throwing in caps at random, or is there a Rhyme, and Reason to their capitalization?

I started researching this one by looking at the original version of the Declaration and a few other, different but contemporary copies. Here’s one: a 1823 William Stone facsimile of the original Declaration. Stone may well have used a wet pressing process (that is, he pressed a contact sheet onto the original, removing traces of ink from the original document for the purpose of making the engraving).

I started here because I wanted to see how consistent their capitalization practices were. As you see, I’ve marked in pink all of the caps that seem arbitrary to me–the C in “Course,” the L in “Laws” and so on. But notice the p in “people” of line #1? (The yellow rectangle above.) That’s capitalized in preceding printed version (from 1776). If you compare the original written version with printed versions, it’s clear that the capitalization pattern isn’t very consistent.

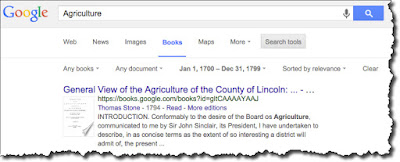

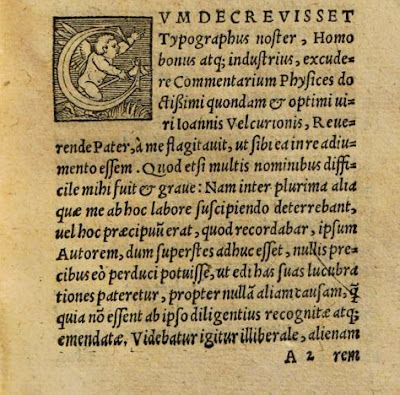

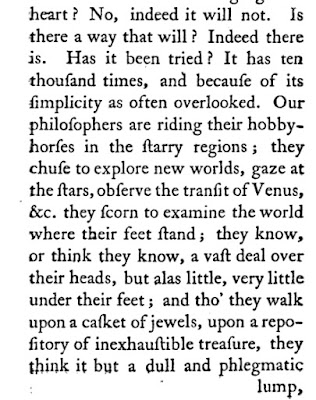

Here are a few pages of books from the past few hundred years: notice how the pattern of capitals change… The first book here from 1539 doesn’t have many capitals at all–a few, but rarely. While later texts add more and more…

|

| 1539 Johannes Velcurio Commentarii in Universum |

|

| 1676 book by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim The Vanity of Arts and Sciences. |

|

| 1774 Bible from St. Andrews special collections. |

|

| 1770 book by John Dove, Strictures on Agriculture. |

|

1774 book by Arthur Young on “A Course of Experimental Agriculture” |

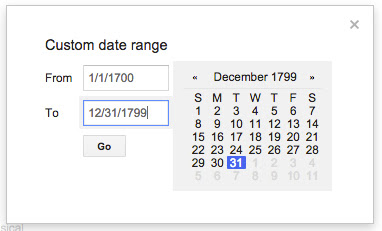

I got these all from Google Books as a way to get to some original content. I just did a search for [Agriculture] since I knew that this was a topic that has been written about for hundreds of years, then I time-restricted the books to particular centuries.

To open the date-restriction in Google Books, you need to click on “Search Tools” and then fill in your dates:

Doing that repeatedly gave me all of the samples from above. By comparing different editions of the same book (or the Declaration), I found that capitalization practices varied quite a bit over time, and even across editions. (For that fact, spelling varied as well. On the tenth line from the bottom. Jefferson spelt British with two ‘T’s. It’s rendered in the more current spelling elsewhere. ‘Neighbourhood’ is written in the English form with what we consider an extra “u.” Later versions of the Declaration have standardized the spelling and (to an extent) the capitals.

But to learn more, I first did a search for:

[ capitalization Declaration of Independence ]

and found a nice article on the Grammarly.com site about caps in the Declaration. In there, they point out that “The non-standard capitalization of key words, on the other hand, functions to heighten emphasis and dramatic effect. Examples of the liberal use of capitalization in the Declaration of Independence include: “Laws of Nature” “Form of Government” “Safety and Happiness” “Standing Armies” “Free and Independent States”

In other words, there aren’t strict guidelines, but the capitalization was more a typographic means of expressing emphasis.

My next search:

[ history of capitalization ]

leads to a wealth of resources, one of which was the Wikipedia page on Letter Case, which told me that “Other languages vary in their use of capitals. For example, in German all nouns are capitalised (this was previously common in English as well), while in Romance and most other European languages the names of the days of the week, the names of the months, and adjectives of nationality, religion and so on normally begin with a lower-case letter.”

This now starts to move into our next question…

2. Related: How / why / when did our practice of capitalization change to what it is currently? (And, for extra credit, do other countries follow the same pattern of capitalization that we English-speaking types do? For that fact, is the practice of capitalization the same in the US as in the UK?)

Traditionally, certain letters were rendered differently according to a set of rules. In particular, those letters that began sentences or nouns were made larger and often written in a distinct script. There was no fixed capitalisation system until the early 18th century. The English language eventually dropped the rule for nouns, while German kept it.

Continuing down the list of hits from my last query, I found a fascinating thread in the English language section of StackExchange. (If you don’t know StackExchange, it’s well worth visiting. The forums tend to be very high quality, with lots of learned folks exchanging ideas. For any kind of advanced programming, SE is essential. Get to know it! The section on English is described as “English Language & Usage Stack Exchange is a question and answer site for linguists, etymologists, and serious English language enthusiasts.”)

Here’s what is written in that Exchange (by Tucker):

David Foxon’s 1991 Pope and the Early Eighteenth-Century Book Trade is the canonical Work on this Topic.

As to when the rule of capitals for nouns was inherited into English, that perhaps can never be known.

Since German capitalizes every noun there is speculation that this rule has been inherited from there, perhaps via Johannes Gutenberg and his famous printing press via the Gutenberg Bible (note that the Gutenberg press is not the first of its kind as the Chinese and Koreans already had this technology as early as 1000s). This could be where the Germanic rule of capitalizing nouns may have originated since the Gutenberg (and subsequent presses) were all German in origin and their language and grammar rules may have influenced the rules of printed words far and wide.

Capitalized nouns were a common occurrence and can be seen in many instances prior to the 1730s and seems to be a shift at this point. From this first issue of the Gentleman’s Magazine published in 1731. Every noun has been capitalized. This heavy use of capitals seems to be common especially in the printed word. David Foxon wrote in his book entitled Libertine literature in England, 1660-1745 that “… the vogue for heavy caps may be associated with the eighteenth-century culture of sensibility.” Also, “Heavy caps also seem to be associated with the more chatty, conversational style of prose that comes into fashion in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.”

There is a steady drop of capitalizing every noun as can be seen by this volume of the Gentleman’s Magazine printed in 1744. This starts to look familiar with printed and accepted usage by today’s standard.

And do the US and the UK differ in capitalization? Sure. My query:

[ differences between US UK capitalization ]

led me to the Wikipedia entry on Capitalization, which has an extensive listing of the differing practices. Oddly, while acronyms have historically been written in all-caps (e.g., NASA), British usage is moving towards capitalizing only the first letter in cases when these are pronounced as words (e.g. Unesco and Nato), reserving all-caps for acronyms made up of pronounced letters (e.g. UK and USA).

3. What are those funny connectors between characters? What are they called, what pairs of letters have them, and how can I get those on MY computer?

This one is easy. My query:

[ connector between letters ]

tells me that these small strokes between characters are called ligatures. A quick Image search for [ ligature ] shows many different kinds. Here’s a sampler:

Notice that ligatures also include letters that overlap (such as the OC combination above) and letters that blur together (like ӕ).

Now, how do I get these in MY documents?

The simplest way when writing on the web (such as, when I’m writing this blog), is to find an resource that has them all.

The truth is that I tend to use a specialty app (like Illustrator or Word) to get the character, insert the special character in a blank document, then copy/paste it to my target document. This gives a good deal of control over what kind of character you get.

To get a ligature character in MS Word:

1. Have a font that includes ligatures. You probably already have several, even if you don’t know it. Explore a bit and you’ll quickly discover which ones have them (big hint–they tend to be older fonts such as Palatino Linotype).

2. In Microsoft Word, click “Insert” then “Symbol.”

3. On the “Symbols” tab, there should be a “Subset” dropdown list on the right. If there’s not, pick a different font from the “Font” list.

5. Scroll down the “Subset” list until you find a subset called “Alphabetic Presentation Forms.” Or, easier still, click in the list and then press the “A” key on your keyboard until you come to “Alphabetic Presentation Forms.”

6. Somewhere in the characters displayed will be some ligatures, probably fi and fl but maybe others as well. Click one of them, then click “Insert.”

To get a ligature character in Google Docs:

1. To insert a special character, do Insert>Special Characters>

2. Then, do a search for “ligature” in the pop-up menu that appears (note where I entered “ligature” next to the magnifying glass…

Once there, you can insert whatever characters you like, such as:

Now you can do your typographical best!